THE EASTERN RADAR DEFENSE

"SILENT SENTINELS AT SEA"

TEXAS TOWERS

The Air Force originally planned for the towers to be continuously manned by twenty-two men. This number proved to be grossly inadequate; by 1957, a crew, normally consisting of six officers and forty-eight airmen staffed each tower. Not only radar men, but also personnel for plumbing, refrigeration, medical and cooking chores manned the stations.

THE TEXAS TOWER FEATURE ON EARLY NEWSREEL SHOWING THE US NAVY SUPPLING THE REMOTE RADAR POST WAY OUT IN THE ATLANTIC OCEAN

The Air Force occupied TT-2, 110 miles off Cape Cod, in December, 1955. Tower and crew alike suffered the effects of constant vibration from the rotation of the radar antenna and the diesel generators. The surrounding water, and footings driven into the ocean floor even transmitted distant sounds up the steel legs to be amplified through the whole structure.

The Texas Towers were originally equipped with one AN/FPS-3 search radars and two AN/FPS-6 height finder Conception and Approval, 1952-1953. Fastening radar platforms to the ocean floor was first studied in the summer of 1952. MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory analyzed the feasibility of stationing search and height-finding radars on giant metal towers planted at intervals along the ocean bottom, similar to oil-drilling rigs employed in the Gulf of Mexico. Lincoln Laboratory concluded that a cluster of such Texas Towers might, in fact, profitably serve air defense purposes if erected about 100 miles off the northeastern coast of the Atlantic seaboard. There, elevation of the ocean floor, owing to the continental shelf, conveniently afforded areas shallow enough, yet far enough at sea, to be strategically important. Being fixed installations, Texas Towers could accommodate heavy duty, long-range radars like those used on land, instead of lighter, medium range sets like those used aboard picket vessels.

That the preponderant amount of America’s high priority targets were situated inside the U.S. northeastern industrial complex—within easy striking distance of the Atlantic coast—made the stakes involved that much more serious. Advance warning furnished by Texas Towers, in combination with other elements of the growing early warning network, including Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) aircraft together with Navy radar picket ships, promised to reduce America’s vulnerability to surprise attack. Simultaneously, target tracking information supplied by Texas Towers would enable ADC’s control centers to vector fighter aircraft to intercept unknown targets far out at sea, where hostile bombers could be destroyed long before reaching bomb release lines. In conjunction with AEW&C aircraft and Navy picket ships, Texas Towers would contribute to extending contiguous east-coast radar coverage some 300 to 500 miles seaward. In terms of the air threat of the 1950’s, this meant a gain of at least 30 extra minutes warning time of an oncoming bomber attack.1

ADC found no complaint with Lincoln Laboratory’s recommendation that five Texas Towers be installed. Lincoln obligingly named the five sites best suited for positioning radars: (1) Nantucket Shoal (Lat. 40°45’N., 69°19’W., 80foot depth) 100 miles southeast of Rhode Island; (2) Georges Shoal (Lat. 41°44’N. , Long. 67°47’W. , 56-foot depth) , 110 miles east of Cape Cod; (3) Cashes Ledge (Lat. 42°53’N., Long. 68°57’W., 36-foot depth), 100 miles east of New Hampshire; (4) Brown’s Bank (Lat. 42°47’N., Long. 65°37’W., 84foot depth), 75 miles south of Nova Scotia; (5) Unnamed Shoal (Lat. 39°48’N., Long. 72°40’W., 185-foot depth), 84 miles southeast of New York City.

In September 1952, ADC voiced its desire that USAF favorably consider the proposed Texas Tower layout for future implementation. USAF first looked into the legality of positioning fixed radar platforms on the high seas, whereupon the Judge Advocate ruled that no violation of international law would result from their placement adjacent to territorial waters. Upon deliberating on the other aspects concerned, USAF, too, became convinced of their necessity and, in the autumn of 1953. authorized construction of all five. Accordingly, funds were budgeted for them during Fiscal Years.1954 and 1955; the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks was vested with authority to conduct ocean surveys, execute design engineering, draw up specifications, and perform the other services requisite to letting out contract work to the lowest competent bidder.2 Groundwork for Implementation, 1953-1955. All manner of things had to be determined before precise specifications detailing internal and external dimensions—could be drawn up for release to competitive bidders. There was the matter of deciding how many and what types of personnel to people the towers with. Types of equipment to install had to be settled beforehand: not only surveillance and communications kinds for operational purposes, but also food preparation and recreational kinds, among others, for logistic and morale purposes. How to replenish, with some regularity, expendable commodities and other supply items, required thoughtful consideration, so as to strike a proper balance between overloading and under-supplying each tower. These and other questions raised by the concept of sticking Texas Towers radars 100 or so miles from shore constituted problems of no mean proportion, which ADC, in the early 1950’s, speedily came to grips with. Manpower totals for sustaining three-shift, round-the-clock operations was no easy figure to compute. Initially, ADC had in mind remoting tower radar data, via submarine cable, from tower to shore, where the weapons control function of vectoring interceptors would be handled by the crew at the parent ACW shore site. This, accordingly, lessened the number of persons whose presence would be needed for tower duty. First, in September 1952, a crew of 22 men was postulated as a likely number for maintaining continuous operations, presupposing that Texas Towers would have no target identification or weapons control responsibilities. This estimate climbed to 25 in August 1953, to provide technicians for servicing the second of two height-finders programmed. A few months later, in November 1953, the personnel contingent was re-estimated at 27, upped next to 41 in July 1954. It then developed that no submarine cable would be strung for remoting, that existing “slowed down” video could not be made to work properly in its stead, and that too much time would be consumed either fabricating or adapting old equipment to this purpose. ADC therefore was obliged to change heart, electing to program control functions at each tower, together with the attendant increase in personnel this entailed. Until near the end of the decade, when the Texas Towers were scheduled convert to SAGE operations (whereby the Lincoln Fine System, AN/FST-2, would be installed to feed lance data automatically from the tower to specified SAGE centers), the Texas Towers were to operate manually, utilizing GPA-37 consoles for vectoring interceptors to their respective targets. Consequently, personnel estimates were upped again in January 1955, this time to 46 in all, to each tower with personnel enough to handle the control function, along with the other conventional surveillance duties. Space enough was allowed during the stages (late 1954-1955) to accommodate upwards of 72 which was fortunate considering that the size of the personnel force continued growing. In mid-1956, after first tower was erected, the staffing structure was hiked from 46 to 49 officers and airmen for sustaining Texas Tower missions. Even this later proved inadequate by five spaces, as evidenced by a staffing pattern in 1957 calling for a total of 54, composed of six officers and 48 airmen. This large a contingent embraced personnel not only to operate and maintain the surveillance, control, and communications equipment, together with specialists in the plumbing, heating, refrigeration, medical and cooking business to help keep body and soul alive,

but also to fill unique spaces, insofar as ADC was concerned, peculiar to the Texas Tower mission. Into this latter class was categorized the slot for one S/Sgt (Staff Sergeant) “seaman” and one A/lC (Airman First Class) “marine engineman” to handle maritime matters associated with Texas Tower operations. So specialized were some of these maritime support jobs, that ADC, until subsequently discouraged by USAF, showed interest in a 1956 proposal to transfer the entire Texas Tower program—operations, maintenance and all—to the Navy Department.

Besides the commander, who was ordinarily a captain, something like three to four officer weapons controllers (AFSC 1644), together with half a dozen or so airmen ACW operators working under them, and nearly an equal number of radar repairmen under charge of an electronics officer (AFSC 3044), were assigned each crew. Communications operators and technician repairmen were well represented, too. Each crew was divided into three shifts.

One thing ADC insisted on regarding personnel manning was the right to form two crews per tower. ADC desired to alternate on-station tower duty so that no single crew spent more than one month aboard a Texas Tower without time, the following month, spent ashore, when the second of two crews took its month’s turn, on a rotational basis. Tower duty, incidentally, counted as time aggregated on an isolated overseas tour.

But USAF was reluctant to authorize the extra spaces that this two-crew plan entailed. The most USAF would bend, was a 1.5 crew manning ratio per tower. ADC persevered in reaffirming need for a 2.0 crew manning ratio, and eventually resorted to improvising the difference by borrowing from its own resources.3

Determining what kind of equipment to install was more easily determined, particularly with regard to surveillance equipment. Precedents for selecting search and height-finding radars already existed in the form of ADC’s ground-based AC&W sites. Drawing from its experience with them, ADC picked the FPS-3A long-range search set (modified subsequently to the FPS-20A configuration), and two FPS-6 long-range height-finders. For protection from wind, rain and snow, all three antennas were to be enclosed in arctic tower radomes composed of a rubberized dome sprouting bulbously 55 feet in diameter, and supported underneath by a walled framework. These helped characterize the shape TexasTowers finally assumed, silhouetting a clover-leaf profile on stilts.

Ordinarily, installation of a pair of FPS-6 height finders and an FPS-3A search set entailed separating them at least 150 feet apart, for good reasons. If bunched closely together, there was a real danger of mutual electronic interference being generated when radar antennas faced one another. An exception to this rule, however, had to be made aboard Texas Towers, where surface space, of necessity, was constricted. To minimize chances of mutual interference, yet compactly squeeze all equipment atop a relatively small surface, the FPS-3A search set, sandwiched between the other two, was elevated so as to tower above them. The two FPS-6 antennas, moreover, were pointed in opposite directions, one facing toward land, the other toward sea, being slaved together, and to the FPS-3A, for synchronizing movements. As a final measure of precaution, interference blankers were installed to blot out electronic signals emanating from FPS-6 antennas when pointing toward the FPS-3A.4 Tower-to-shore communications presented a problem different from that of radars. There simply was no network of telephone lines conveniently at hand to tap into, as at ACW stations on land. Notwithstanding this, the question was settled long in advance of tower erection time. ADC originally wanted-to string submarine cables from tower to shore at a cost estimated at first to be $1,000,000 per tower. Follow-on estimates that nearly doubled this amount, however, helped doom the submarine cable plan. Another system equally favored by ADC was adopted for primary point-to-point communications: multiple-channel tropospheric scatter radio, described in more detail below.5 After the size of the forthcoming personnel contingent and of the equipment inventory was, for the most part, known, work proceeded on the platform to accommodate them. Beforehand, the Navy Bureau of Yards and Docks had contracted core-drilling work in July 1954 to the De Long Corporation and the Raymond Concrete Pile Company. Feasibility studies, on 18 June 1954, were farmed out to the architect-engineering firms of Moran, Proctor, Mueser and Rutledge of New York City, and the Anderson-Nichols and Company of Boston. These studies were soon completed and, by October 1954, their results submitted. Hereupon, the Bureau of Yards and Docks contracted with the same firms to formulate the engineering and design work for five towers. They were expressly designed to withstand 125-mile per hour winds and 35-foot high waves.

Texas Tower 2. Responsibility for constructing the first Texas Tower was entrusted to Bethlehem Steel Company. By then, each of the five approved sites had been designated as follows: Cashes Ledge was named TT-1 (for Texas Tower 1); Georges Shoal, TT-2; Nantucket Shoal, TT-3; Unnamed Shoal, TT-4; and Brown’s Bank, TT-5. This numbering sequence, however, was not indicative of site-erection priorities. Indeed, it was TT-2, Georges Shoal that ADC chose for its first Texas Tower. Situated some 110 miles east of Cape Cod, the TT-2 unit, besides enjoying a location in shallow waters that would help facilitate its erection, was to be among the first of ADC’s radar units to tie into the emerging SAGE network.6

THE NEW YORK AIR DEFENSE SECTOR WITH THE TWO TOWERS TT-3 TT-4 JUST OFF LONG ISLAND TT-3 SERVED BY THE ELECTRONIC WARNING SQUADRON BASED OUT OF MONTAUK AIR STATION

|

| TEXAS TOWER No.3 OFF LONG ISLAND |

Transporting the first platform from shore to site was a toilsome task. There was trouble enough launching it into water, let alone hauling it to sea. Yet, by June 1955, it was successfully floated and fitted for its sea voyage. Responsibility for towing it to site and then erecting it, was vested in the Raymond and De Long Companies, who embarked with their charge on 12 July 1955. Within two days time, they arrived on site. Hereupon, temporary legs were dropped to the shoal (about 55 feet under water); the tower platform was jacked up to rest on the temporary legs high above the water, while the three permanent legs, or caissons were readied. Each of the three tubular legs was designed for lasting support, measuring over 160 feet long, the first 48 or so feet of which were ensconced snugly into the shoal, the middle 55 feet of which remained immersed in water, and the top 60 or so feet of which rose above the water’s surface, lifting the platform high and out of harm’s way. The legs were versatile enough to be logistically, as well as architecturally purposeful. For inside each steel leg was incased a 140-foot long steel tube six feet in diameter where thousands of gallons of fluid reserves, mostly water and fuel oil, might be stored, surrounded by a jacket of concrete over two feet thick. One of the three hollow legs contained seawater tapped for conversion to drinking water. To this end, distillation equipment was included for producing several gallons of fresh water per minute.8 By the end of 1955, TT-2 was assembled, with bolts tightened and the rest shipshape enough for USAF to assume beneficial occupancy. This it did, effective 2 December 1955. The FPS-3A and twin FPS-6 height radars, as programmed, were brought aboard and installed. They detected targets of B-47 size, flying about 50,000 feet, up to 200 nautical miles away. But the same targets flying at low altitudes say 500 feet—because of line-of-sight radar characteristics, were discernible by radar only up to 50 nautical miles away. It was for this reason, among others, that airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft later patrolled certain off-shore stations to cover low-altitude radar gaps over looked by Texas Towers, picket vessels, and shore-based radars.9

Along with the radars arrived the communications equipment, without which Texas Towers, being unable to transmit their findings to shore, would be incapacitated. Foremost among this equipment came the point-to-point, FRC-56 tropospheric scatter system. Three parabolic-disk antennas, measuring 28 feet in diameter, were mounted vertically, side by side, along the platform edge supporting the operations deck. Two at a time were utilized for transmitting messages, while all three combined received them. The signals were deflected from the tropospheric layer of Earth’s atmosphere, between the 30,000 and 60,000-foot level. A wide spectrum of ultra-high frequencies was thus exploitable without recourse to expensive intermediate relay stations. Normally unaffected by atmospheric disturbances, the tropospheric scatter radio system worked well in the manual system for distances up to about 200 miles, and was intended to serve equally as well for automated SAGE communications later to come. At either end of the system, telephone circuits were patched in so that voice communications could be reliably maintained.

Apart from this primary point-to-point system, there was installed conventional BF radio equipment for tower-to-shore backup communications, and UHF and VHF radio equipment for tower-to-air communications. Teletype, cryptographic, telephonic intercommunications and public-address systems were incorporated as well, together with certain aircraft radio navigational devices. GPA-37 equipment was integrated to facilitate weapons control operations. To power the communications, navigation and radar equipment thus brought aboard, eleven 250 KW diesel generators were rigged so that less than half of them, operating in unison, would supply sufficient electricity during any given time. Air conditioning units were furnished to prevent certain of the equipment from over-heating.10

Site P-10 (762 ACW Squadron) at North Truro AFS, Massachusetts, was designated the parent station for TT-2. Operational concepts governing their relationships were diligently spelled out in a full-dress operations plan, first published by ADC in July 1954, later revised in July 1956. Other matters were carefully worked out, such as methods for transportation and supply. Two H-21B helicopters per tower were authorized by USAF, four of which were based at Otis AFB and two, at Suffolk County AFB. The twin-rotor H-21B had a theoretical capacity for carrying 10 passengers or 2,000 pounds of freight. When equipped with necessary flotation and survival gear, however, the H-21B’s capacity was cut to eight persons or 1,550 pounds of freight. Other cargo, particularly POL, was furnished periodically by ship. Fuel, food and lubricants,were stocked to provide at least a 30-day reserve; spare parts were on hand for operational equipment to last 45 days On 7 May 1956, TT-2 achieved the status of a limited operationally ready aircraft control and warning station. For purposes of furnishing logistical support for TT-2, and for the others when the need arose, the 4604 AC&W Squadron (Texas Towers) was activated 8 October, 1956 at Otis AFB, Massachusetts, which two months later (December 1956), was re-designated the 4604th Support Squadron (Texas Towers).11

Texas Towers 3 and 4. Meanwhile, by November 1955, bids for the next two towers had been accepted. Construction contracts for both of them were awarded J. Rich Steers, Inc. of New York City in collaboration with Morrison-Knudsen, Inc., of Boise, Idaho. Except for minor changes (including longer legs and increased storage capacity for diesel oil), these two practically duplicated the configuration and basic arrangement of TT-2.

Because of future commitments to integrate Texas Towers into upcoming SAGE centers during the late 1950’s, ADC picked TT-3 at Nantucket Shoal, and TT-4 at Unnamed Shoal, for its next two towers. This left only TT-1 (Cashes Ledge) and TT-5 (Brown’s Bank) unaccounted for. USAF, for purposes of economizing, was anxious to rid the program of them both.

At first, ADC resisted all attempts in this direction. Then, in late 1956, because of the promise of increased off-shore radar coverage by coastal AC&W squadrons in the vicinity, where TT-1 and TT-5 were scheduled to go, ADC agreed to drop TT-1 and TT-5 from all further consideration, leaving three towers, TT-2,TT-3 and TT-4, in the program.12

In 1956 and 1957, work proceeded on TT-3 and 4. Platform and legs of TT-3 were readied by mid-1956, launched the night of 7 August 1956, and towed to Nantucket Shoal and erected that same month. On 29 November 1956, ADC assumed beneficial occupancy. Next month the superstructure and main supports of TT-4 were under construction at South Portland, Maine. These were completed by mid-1957, then, starting 28 June 1957, were towed to sea and placed at Unnamed Shoal. ADC gained beneficial occupancy in November 1957.

The New Life. During these same years (1956-1957), personnel serving at TT‑2 — then functioning manually on a limited operational status—were learning of peculiarities uniquely associated with Texas Tower duty. For one thing, the metal superstructure seemed to vibrate constantly. As the FPS-20A long-range radar antenna (converted from the original FPS-3A model), continued unceasingly to spin (except when out of commission for maintenance), the diesel generators, to grind out their power, and the other equipment, to crank away at their appointed tasks, TT-2 rattled vibrantly from the ordeal. Standing like a three-pronged tuning fork, the tower resonated with noises that spread farther, and amplified greater, than initially occasioned by their source. Matters were not improved when, every half-minute or so during the frequent fogs, the dismal-sounding foghorn croaked out its forlorn message.

Still worse, since it affected operations, was the phenomenon of temperature inversion suffered mostly in summertime. This caused loss of radar coverage, creating, in certain instances, permanent echoes that obscured or distorted radarscope reception. On occasion, equipment components generated electromagnetic disturbances that interfered with, or disrupted, operations of other electronics apparatus. Notwithstanding these and other shortcomings, tower crews became inured to those problems not susceptible of change. And TT-2, effective 17 April 1958, became fully operational manually, then in September 1958, operational as a SAGE unit. TT-3 followed suit in October 1958. TT-4, in mid-April 1959, was declared manually operational, and in April 1960, SAGE operational. Cost of the towers, including platform, legs, radars and communications equipment was reckoned at around $13 million each, and with operating expenses figuring about $1.5 million annually thereafter. TT-3 reported to, and comprised an annex of the 773rd AC&-W Squadron (Montauk, New York);

|

| THE 773rd MONTAUK AIR STATION |

|

| RADAR DISH ABOARD TEXAS TOWER |

|

| RADAR RECEIVER ON TEXAS TOWER |

Communications Difficulties. While the three towers, by 1959, were thus up and operating, all was not well with them. One of the main difficulties centered on the FRC-56 tropospheric scatter communications system. When functioning in the manual system, employing voice communications, tropospheric radio proved sufficiently effective. But faulty communications ensued after FST-2 equipment was installed to automate communications for SAGE operations, wherein tower-to-shore communications were transmitted and received, not by voice, but by pre-coded, digitally computed electronic signals for automatic assimilation by SAGE computers. Since SAGE shore computers were calibrated to reject all except perfectly accurate inputs, the tropospheric system, as then in operation, simply could not accomplish the task. It was decided about this same time not to replace each FPS-20A search set and twin FPS-6 height finders with Frequency Diversity FPS-27 search and FPS-26 height finder sets, as programmed theretofore, because of the expense involved. The FPS-20A’s at TT-2 and TT-3, instead, were later modified with GPA-103 equipment in late 1960, incorporating certain ECCM devices that reshaped their FPS-20A to the FPS67 configuration.

Several remedies, meanwhile, were suggested to correct the problem with communications. One proposal reverted to ADC’s original plan: stretching a submarine cable from shore to each tower. Another solution proposed by the MITRE Corporation looked more toward refining the existing apparatus, so that tropospheric radio, with the addition of Code Translation Data Service (CTDS), would still bear the burden of primary tower-to-shore transmission and reception. CTDS would tolerate greater signal level variations than existing subsystems. American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), which frowned on this idea, was approached with a proposal to take charge, on a contract basis, of maintenance and operation responsibilities for the tropospheric system. While solutions to this problem were under consideration, the three Texas Towers reverted to operating as a manual adjunct, employing voice communications, in the far-flung semi-automated SAGE network.14

In 1960, a proposal was advanced that perhaps would have solved some part of the communications problem, namely the installation aboard Texas Towers of ALRI (Airborne Long Range Inputs) equipment designed to automate the communications process. This plan was soon discarded, for several reasons, not least of which was the dearth of available space for accommodating the ALRI equipment. The same year, all further consideration was dropped of stringing submarine cables, or adding CTDS, leaving only the prospect of AT&T taking charge of maintenance and operations. Antenna realignments combined with improved maintenance, supply, training and operating procedures enhanced tropospheric communications appreciably during 1960, and to all intents and purposes rendered them satisfactory for SAGE as well as for manual operations.15

|

| TEXAS TOWER No.4 |

Tragedy of TT-4. A problem of inherent stability at Texas Tower 4 loomed so large at this time that it overshadowed all previous Texas Tower problems. Ever since TT-4 was towed to site in mid-1957, it had become an engineering nightmare. To begin with, supports for TT-4 had been made somewhat differently from those fabricated for TT-2 and TT-3, chiefly because of the extra depth involved. Whereas TT-2 and TT-3 stood firmly in relatively shallow waters, 56 and 80 feet, respectively, TT-4 stood in water two to three times deeper, 185 feet to be exact. A series of underwater bracing-s were made to compensate for the extra stresses incurred. But in the process of towing TT-4 to site in June-July 1957, two diagonal braces, vital to lacing the three legs snugly together, were lost. The contractor and the Bureau of Yards and Docks decided to improvise repairs on the spot, rather than return to shore for reworking defective portions. The original design strength, consequently, was not restored. From the time it was erected, Texas Tower 4 wobbled some when under stress caused by brisk winds and waves. Platform motion became the rule rather than the exception. The Navy, in late 1958, conducted underwater surveys of TT-4’s supports, resulting in the discovery that certain collar connection bolts either had sheared or worn loose. The problem was aggravated because the defective portion weakened not only its immediate area, but also shifted considerable stress onto non-defective members. From late 1958 to May 1959, with at least six interruptions due to storms, the contractor effected repairs that stabilized the platform for several months. Four successive storms struck in the winter of 1959-1960, which threatened to undo tower stability all over again. In early 1960, another underwater team was sent down to take stock of things and found certain pins and connections irreparably damaged; whereupon a set of above-water bracings were manufactured and, by August 1960, applied. According to the contractor, original design strength was restored to TT-4 — it could withstand winds up to 125 miles per hour and breaking waves up to 35 feet high. Scarcely a month elapsed, however, when Hurricane “Donna” (12 September 1960) whirled in at forces exceeding design specifications: 132mile per hour winds and breaking waves exceeding 50-foot heights. TT-4, evacuated of all personnel two days before, survived “Donna,” but not without first shaking and rocking a great deal from the impact. Part of TT-4’s superstructure was destroyed; worst of all, below-water bracings were fractured, cutting overall strength to 55 per cent of what it had been built up to prior to “Donna.” Further examination of above and below-water components resulted in a decision to undertake extensive repairs in the spring of 1961. 1 February 1961 was established as the date for complete evacuation of TT-4. Meantime, a maintenance crew of 28 persons -- 14 USAF and 14 contractor repair personnel—were stationed aboard to perform certain repair work. Then on 14 and 15 January 1961, TT-4 was again caught in a storm that battered the tower with winds up to 85 miles per hour and waves up to 35 feet high thrashed its legs. Finally, TT-4 could stand no more. At about 1920 hours the night of 15 January, one of its three legs snapped in half; the remaining two thereupon broke, and the platform, with all hands aboard, sank to the ocean’s bottom.16

Demise of TT-2 and TT-3, 1961-1964. The tragedy of TT-4, as much as anything else, sealed the fate of TT-2 and TT-3. While both remaining towers were immediately checked for safety and structural strength, and pronounced sound in this regard, their days were numbered. This was first hinted in March 1961, when Lieutenant General Robert M. Lee, ADC commander wrote:17

At this time there is no valid reason for abandonment of Texas Towers No. 2 and 3. However, in view of the inherent danger and the current inability to evacuate safely during storm conditions, this headquarters, in conjunction with Headquarters NORAD, will continue to consider the operational requirement for these towers. There is a possibility that, after the ALRI (Automatic Long Range Input) System becomes operational in AEW&Con aircraft, sufficient reliable coverage may be achieved so that the contribution of Texas Towers 2 and 3 to the air defense system will be reduced. In this event, shutdown of the towers, with a resultant elimination of the inherent risk, and saving in money and manpower, may be possible. On the basis of technical advice now available there is no concern for the stability of the towers, but should the result of the engineering survey indicate the existence of any deficiencies, immediate action will be taken to discontinue their operation.

Ultimately, it was decided to do just that: phase out TT-2 and TT-3 when ALRI equipment became operational in the AEW aircraft wing based at Otis AFB, Massachusetts. ALRI, in essence, would automate much more of the off-shore surveillance and weapons control functions along the Atlantic seaboard, and with ALRI-equipped aircraft covering virtually the same area as TT-2 and TT-3, the two towers would become expendable commodities. Until ALRI became operational. However, the command sought to implement the best of all possible escape methods aboard the surviving towers, so that the TT-4 episode would not be repeated. Several experimental methods were considered and all but one were ruled out a — watertight escape capsule. Just such a survival capsule, capable of accommodating seven persons, with food and oxygen enough to last 15 days, was designed by the Electric Boat Division of General Dynamics. Two were made, one for each tower, and they were installed in October 1962. Meantime, tower evacuation criteria were revised, so that all would depart except a seven-man emergency stand-by crew whenever 50-knot winds or 35-foot waves were forecast. A seven-man standby crew was necessitated because of a complication occasioned by Soviet trawlers, which often loitered close by the towers. Without a standby crew to keep guard, Soviet sailors might try to board a fully evacuated tower, then claim possession on grounds of salvage rights. If worse came to worse as regards tower stability during a storm, the seven-man standby crew could scramble into the survival capsule for protection. Even the seven-man crew would evacuate when 70-knot winds, or more, were in the offing. The Coast Guard, in an on-again, off-again commitment, promised to position a vessel, if available, near completely evacuated towers to prevent unauthorized boarding by Soviet mariners.

All this, while the Atlantic Ocean, as if impatient to rid it of the troublesome towers, attacked them from above and below. A succession of storms struck during 1962 and 1963 that forced abandonment of the towers a number of times. Between October 1961 and March 1962, for instance, the towers were evacuated ten times, resulting in loss of the equivalent of 120 operational days. Still later that same year, TT-2 and TT-3 experienced many more evacuations. Also, TT-3 lost at least two inflatable radomes, one of which was blown off the FPS-67 search set in the summer of 1962, and the other of which collapsed over a FPS-6 height-finder in January 1963. Simultaneous with these forces working above, strong ocean currents worked steadily beneath to undermine the foundation of the two towers. Scouring of serious proportions resulted, flushing away rock fill supporting the three legs of each tower down to a depth of 10 feet. Even rock-fill replacement leveled around them in November 1961 failed to stay the action of these underwater forces. The towers, consequently, became far more susceptible to being uprooted by storms of hurricane strength.18

At last, in 1963, ALRI stations became operational in the Atlantic AEW&C aircraft fleet. The JCS, in January 1963, authorized the inactivation of the towers. No longer having a need for TT-2 and TT-3, and still mindful of the catastrophe at TT-4, ADC ordered the two towers dismantled. TT-2 was first to go, being decommissioned 15 January 1963, then stripped of its communications and electronics equipment. Its three legs were dynamited; but the platform, rather than float to shore, plunged to the bottom, denying one salvage company the fruits of its preparations. It was as if the capricious Atlantic, vindictive to the last, pulled down another victim to its murky bottom. TT-3 was decommissioned 25 March 1963, and shortly relieved of its radars and communications equipment. Special care was taken in mid-1964 to save TT-3’s platform, the bottom deck was pumped full of urethane foam, then sealed, to insure floatation. On 6 August 1964, the three legs were blasted out from beneath it, whereupon TT-3 platform plunged into the ocean; cork-like, it then rose to the surface, enabling salvage crews to drag it shoreward. Once and for all, the episode of Texas Towers in air defense was brought to a close.19

|

| IN MEMORY OF THE 28 USAF AND CIVILIANS LOST WHEN TT-4 WENT DOWN INTO THE OCEAN WITH NO SURVIVORS DURING A STORM |

1. ADC Historical Study No. 10, Seaward Extension of Radar 1946-1956, pp. 71-75; ADC, Operational Plan for Texas Towers, 20 Jul 1954 [HRF]; USAF Historical Study No. 126, The Development of Continental Air Defense to 1 September 1954, p. 722. Ltr, ADC to USAF, “Extension of Radar Coverage in the Northeast Coastal Area,” 24 Sep 1952 [Doc 91, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of,ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; USAF Plan, “Planning Guide for Implement of Texas Towers,” 16 Nov 1953 [Doc 93, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 19551; Ltr, USAF to ADC, “Air Defense Program Requirements,” 11 Jan 1954 [Doc 94, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; Ltr, USAF to Bureau of Yards & Docks, ‘IFY 1955 Advance Planning Directive - Texas Towers,” 8 Mar 1954 [Doc 95, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955); ADC Historical Study No. 10, pp. 71-72; Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1961, P. 70; USAF Historical Study No. 126, pp. 72-73.

3. See Appendix A for Texas Tower manning structure; Ltr, ARDC to ADC, “Project Texas Towers,” 26 Sep 1952 [Doc 90, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; Ltr, ADC to USAF, “Texas Towers,” 24 Aug 1953 [Doc 92, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; USAF, “Planning Guide for Implementation of Texas Towers,” 16 Nov 1953 [Doc 93, Dov Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; IOCY M&O (ADC) to C&E, et.al., “Change to Detachment Manning to be for Texas Towers,” -27 Jan 1955] IOC M&O, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; ADC, “Operational Plan for Texas Towers,” 1 Jul 1956 [HRF]; Ltr, EADF to ADC, “Information for Guidance of Officers and Airmen Selected for Assignment to 762ACWRON w/Duth Station at Georges Shoal Tower Annex (T-2),” 23 Nov 1956 [HRF]; ADC Historical Study No. 10, pp. 80-82; Ltr, ADC to USAF, “Request for Headquarters USAF Guidance on Texas Tower operation and Maintenance,” 26 S.ep 1956 [Doc 37 in Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 19561; Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955, pp. 34-38; Ltr and Ind, ADC to ARDC, “Radar Video Remoting,” 12 Jan 1955 [Doc 97 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 19551; Ltr and Incl, RADC to AF Cambridge Research Center, “Use of GPA-37 with Texas Towers, n.d., ca. Feb 1955 [Doc 99 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]ADC, Logistic Support Plan for Texas Towers, 12 Mar 1956’[Doc 140 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1956]; Hi-s-t-o-T-ADC, Jul-Dec 1956, pp. 44-45; Ltr and Incl, ADC to USAF, “Request for Headquarters USAF Guidance on Texas Tower Operation and Maintenance, 26 Sep 1956 [Doc 37 in Hist of ADC,, 9 Nov 1956 to Ltr and Incl, ADC to USAF, “Request for Headquarters USAF Guidance on Texas Tower Operation and Maintenance,” 26 Sep 1956 [Doc 38 in Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1956]; C&E Digest, Aug 1957, pp. 4- 4. Ltr, ADC to USAF, “Texas Towers,” 24 Aug 1953 [Doc 92, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; C&E Digest, Jul 1957 pp. 13-15.

5. See Appendix B for Texas Tower Equipment List;

Ltr, ARDC to ADC, “Project Texas Towers,” 26 Sep 1952 [Doc 90,

Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 19551; USAF, “Planning

Guide for Implementation of Texas Towers,” 16 Nov 1953 [Doc

93, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; Ltr, Rome Air

Def Center to ADC, “Improvement and Modifications to Production

AN/GPS-37,11 19 Oct 1954 [Doc 100, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC,

Jan-Jun 1955]; Ltr and Atch, MIT to ADC, 24 Feb 1955 [Doc 112, Doc Vol

XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 19551; ADC, “Operational Texas Towers,” 20 Jul 1954 [HRF); ADC, Plan for Texas Towers,” 1 Jul 1956 [HRF]. “Operational Plan for Texas Towers,” 1 Jul 1956

6. ADC Historical Study No. 10, op.cit. , p. 74; “Last of the Texas Towers, AU Review, Vol XVI, No. 1 (Nov-Dec 1964), pp. 92-94; Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1961, pp. 70-73.

7. ADC Historical Study No. 10, op.cit., pp. 74-76: “Last of the Texas Towers” AU Review, op.cit. , p. 93; C&E Digest, Jul 1957, 13-15.

9 . EADF, “Operational Plan Texas Tower No. 2,11 1 Sep1955, P. 2 [Doc 98, Docs Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955 ].

10. C&E Digest, Jul 1957, pp. 13-15 and Aug 1957, pp. 1-6.

11. ADC Historical Study No. 10, op.cit., pp. 76, 82-84; ADC, “Operational Plan for Texas Towers, 20 Jul 1954 and 1 Jul 1956 [HRF]; Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955, pp. 34-36; Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1955, pp. 67-68; Hist of EADF, Jan-Jun 1956.pp. 64-68; Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1956, p. 64-68 45; ADC, Logistic Support Plan for Texas Towers, 12 Mar 1956 [Doc 140 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1956.]

12. ADC, IOC from ADMEL-3, “Trip Report-Texas Towers, [Cont’d] 26 Sep 1955 [Doc 107, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, JanJun 1955); Msg COOPR 30332, CINCNORAD to USAF, 25 Oct 1956 [Doc 109, Doc Vol XIII, Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 19551; Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1956, pp. 42-43; Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1956, P. 37; Ltr, USAF to ADC “Operational Plan for Texas Tower,” 17 Jun 1955 [Doc 80 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; Msg AFOOP OP D 55901, USAF to ADC- 30 Jun 1955 [Doc 100 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; Msg ADOPR 3645, ADC to USAF, 2 Aug 1955 [Doc 103 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1955]; IOC, ADAIE-CA to ADAIE-C, “Construction’Schedule Texas Tower 3 ...” 8 Aug 1956 [Doc 33 in Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1956.]

13. Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1955, p. 39, Jan-Jun 1956, pp. 37-38, Jul-Dec 1956, pp.. 41-47; Hist of EADF, Jul-Dec 1956, pp. 69-74, Jan-Jun 1958, pp. 49-50; Hist of ADC, JanJun 1959, pp. 58-59, Jul-Dec 1959, p. 43; IOC, ADAIE-CA to ADAIE-C, “Construction Schedule Texas Tower 3...,” 8 Aug 1956 [Doc 33 in Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1956]; Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1961, pp. 72-73; C&E Digest, Aug 1957, pp. 1-6; IOC, ADOCO-C to DCS/0, “Report of Staff Visit,” 27 Aug 1956, p. 2 [Doc 32 in Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1956]; C&E Digest, Nov 1958, pp. 4-6; C&E Digest, Apr 1959, p. 14; Ltr, ADC t5-USAF, “Operational Survey of the 26 Air Division (SAGE),” 5 May 1959 [Doc 70 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1959].

14. Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1959, pp. 59-64, Jul-Dec 1959, pp. 43-46, Jul-Dec 1960, P. 70; Hist of EADF, Jan-Jun 1958, P. 51; Msg EAOCE-ER 1671, EADF to ADC, 11 Sep 1958 [Doc 73 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1959]; Hist of EADF, JanDec 1959, P. 97; C&E Digest, Nov 1961, p.2; Msg ROV-225, ROAMA to AMC, 3 Jul-IDTT-rDoc 70 in Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1960]; Western Elect Co., and USAF SAGE Project Office, Progress Report of USAF Air Defense SAGE System, pp. 19, 85, 1Dec 1957, p. 101; Jul 1958, pp. 35, 43, 118; 1 Jan 1959, pp. 20, 81; and 1 Oct-1959, pp. 19, 85.

1515.Hist of ADC Jan-Jun 1960, pp. 48-49; Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1960, pp. 67-68; Joint Test Staff for SAGE Cateory III Evaluation, Final Report, n.d., ca. 1960, p. U-14 [HRF].

16. Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1960, pp. 70-75.: Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1961, pp. 69-84; ADC, “Report of Proceedings of a Board of Officers - Loss of Texas Tower No. 4,11 4 Mar 1961 [Doc 110 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1961]; Senate Hearings, Inquiry into the Collapse of Texas Tower No. 4, Hearings Before Senate Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services, 87 Congress, lst Session, May 3-17, 1961

(Washington:GPO, 1961) [Doc 113 in Hist of ADC, Jan-Jun 1961],

17. Ltr, ADC to USAF, “Report of Board of officers, Texas Tower No. 4,” 4 Mar 1961 [HRF]. 18.Hist of ADC, Jul-Dec 1961, pp. 78-85; NORAD/CONAD Historical Summary, Jul-Dec 1962, pp. 23-27; FORM RESTRICTED DATA, USAF, Current Status Reports, Mar 1962, p. 3-20, Apr 1962, p. 3-20, May 1962, p. 3-19, Jun 1962, p. 3-19, Aug 1962 p. 3-18, Sep 1962, p. 3-16 [HRF]; ADC to ADC Staff Agencies, “USAF Current Status Report - September 1962, “26 Oct 1962 [HRF]; C&E Digest, Nov 1961, pp. 1-5; ADC, Prog Mgt Div, Weekly Act Rept, 14-20 Sep 1962 [HRF]; Ltr, ADC to ADCCS, “Status of Texas Towers 2 and 3”,11 28 Nov 1962 [HRF]; Msg BOOAC-E 0480, BOADS to 26 AD, 4 Sep 1962 [HRF]; Msg AFOOP-DEWC 60997, USAF to ADC, 10 Dec 1962 [HRF]; Msg 260OP-GP 2246, 26 AD to ADC, 17 Dec 1962 [HRF]; Also AFOOP-DELWC 66098, USAF to ADC, 5 Jan 1963 [HRF]; Msg 260AC-E 0622, 26 AD to ADC, 11 Jan 1963 [HRF]; Msg 26IFS 01-91/631 26 AD to ADC, 17 Jan 1963.[HRF].

19. “Last of the Texas Towers, AU Review, op.cit.,

A still from the 1964 government produced film,

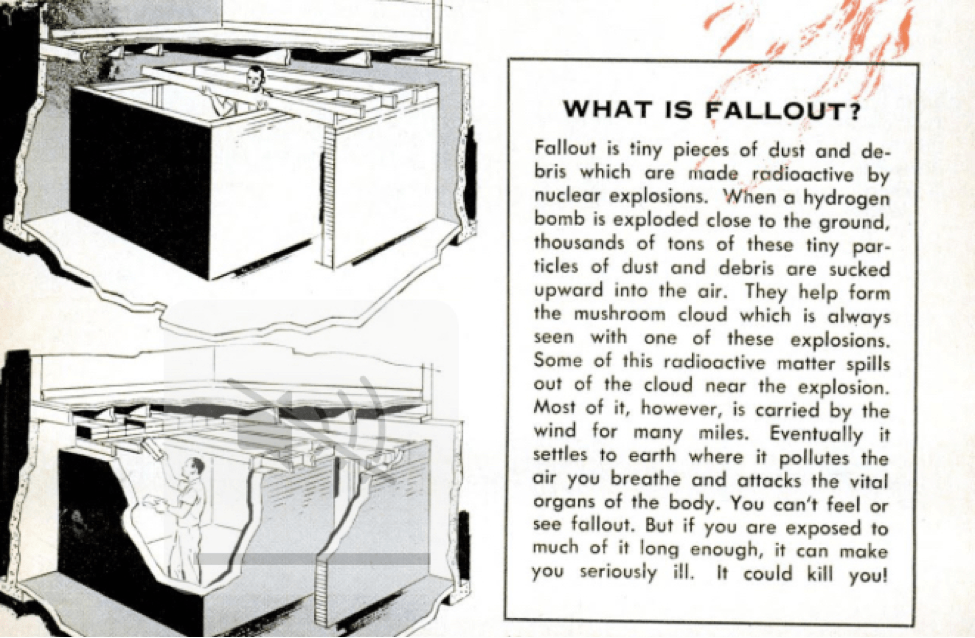

A still from the 1964 government produced film,  An October 1960 feature in Popular Mechanics provided educational advice on fallout and how to avoid it.

An October 1960 feature in Popular Mechanics provided educational advice on fallout and how to avoid it. Idealized American fallout shelter, around 1957. Image via Wiki Commons

Idealized American fallout shelter, around 1957. Image via Wiki Commons